|

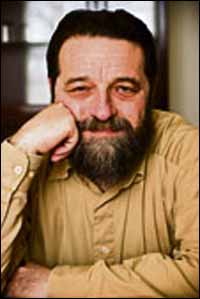

PROFILE How Konstanty wrote his name in Polish history | |

FORMER American president Harry Truman is reported to have said: "Decisions are made by those who turn up."

Jewish journalist Konstanty Gebert turned up to the Polish Round Table Talks in 1989 and helped to establish democracy in a country bullied, butchered and occupied for more than half a century. He organised the underground press during the 1980s, when the first non-communist trade union in the eastern bloc, Solidarity, was coming to the fore and the Iron Curtain was gradually being eviscerated. Konstanty was born in 1953, the same year the Soviet Union's murderous dictator Josef Stalin died. While his parents were Jewish, the family were "so assimilated we didn't even need to deny we were Jewish". Today he is observant, but, growing up under the brutal misrule of the communists, he barely understood his own people's history. His parents, Boleslaw and Krystyna, were ardent communists. His mother fought for the Soviet Union in the Second World War while his father returned from America after the war to ride the ascending communist wave. Krystyna was, according to Konstanty, "very effective at killing Germans". He explained: "My mamela, who spent the rest of her life remaking herself as a lady, literally fought for my right to be born." Casting his gaze on the collective agony of Poland's Jews, Konstanty said: "The Jewish community was traumatised by the war and by post-war anti-Jewish violence. "Jews were seen as supporters of the communist regime. The majority hated them. Killing them seemed a patriotic act. "Being Jewish at that time in Poland was not safe. It was a double trauma - of the past and the present." He said that there were three types of Jews in Poland during the early communist days. "You had the Jewish communists," Konstanty recalled. "They were people who would be active in left-wing Jewish organisations, speak Yiddish and turn their attention towards the Jewish street. "Then you had the communists who happened to be Jewish and often tried to conceal their identity. "And there were the Zionists who believed that 'the solution is not left of here, it is south of here'." Konstanty was from a "good communist background". His father, commonly known as Bill, was a top party official. In America he had established the Communist Party, edited left-wing newspapers and even appeared in nine intercepted KGB messages in 1944. On his return to Poland, he reached the heights of the politburo, eventually being appointed the Polish ambassador to Turkey in 1960. Konstanty's family eschewed traditional Judaism. "It was totally anachronistic," the 59-year-old declared. In his early teens however, his Jewish heritage came hurtling at him like a bullet. Party general secretary Wladyslaw Gomulka waged an anti-Jewish political campaign in 1968, purging the party's upper echelons of Jews, following the Soviet Union's withdrawal of diplomatic relations with Israel due to the Six Day War. Within three years, 12,927 Poles of Jewish ancestry had emigrated. Konstanty said: "That was my first interaction with Yiddishkeit. I got kicked out of high school for being Jewish, though the official explanation was that I was a Zionist. "It was vicious. It was brutal. Antisemitic hate propaganda was pouring from the media. "The feeling was that this might be the 1930s all over again. "But I discovered that my Judaism counted. I didn't know what it was and I didn't know how to find out." With the study of Jewish history out of favour, he easily acquired "bucketfuls" of books to study, including classic Yiddish literature translated into Polish, from second-hand book stores. He said: "For the first time I was reading about the people I knew. "It was mind-blowing. Eventually I ran into distant cousins in America in 1971. They were ba'al teshuva types (returnees to religion). "That's when I had my first Shabbat and discovered that people actually do this." The wheels of his return to Judaism were in motion. Trained as a psychologist, he had a palpable thirst for understanding. Out of a quest to reinvent Polish Jewishness, a group of Jews, led by Konstanty, established the Jewish Flying University. Away from the prying eyes of the secret police, they would meet in private apartments in Warsaw for studies and discussions. "It was part study, part group therapy," he recalled. "It was the first occasion in public for many of us to say that we were Jewish. It was emancipating." When the university disbanded after martial law was declared in 1982, Konstanty went underground with the Solidarity movement. He described the atmosphere of the pro-democracy union with a euphoria that reflected the age. Those involved were ushering in an era of hope, freedom and revolution that would not culminate in a repressive state. "Nothing comes remotely close, it's as good as it gets," Konstanty recalled. "Almost until the end we never thought we'd live to see the day when communism would end in Poland. "We thought that if we were to play our role well then maybe our kids would get a better chance. We knew we were making history. "Everything that has happened since then has been miraculous." As part of the Polish Round Table Talks, Konstanty and other opposition leaders negotiated with the communist government from February to April, 1989. They achieved remarkable concessions. Independent trade unions were legalised, a president would be elected for six-year terms and representative government in the form of a bicameral legislature would be created. Solidarnosc (Solidarity) dominated the vote on June 4, 1989 - the first free elections for more than six decades - winning 99 of the 100 Senate seats. "We were sitting at the same table with people who were trying to arrest us for the last 10 years," Konstanty recalled. "It started off with them being in power, allowing this ragtag bunch of workers and intellectuals to sit at the same table as them. "Eventually, the interior minister would duck when he saw me. We won and they knew it." With the future of the nation on their shoulders, they could not shirk the responsibilities of power. He explained: "We were righteous at the beginning, but then we were scared. We desperately needed the negotiations to succeed. If we had not, then the system would have collapsed and it would have been bloody. "It was not about revenge. We needed to find a solution acceptable to both sides. We thought of ourselves as the people and them as Muscovites." For the Jewish community, it was also a time for reinvention. "The community went through an extremely difficult transformation," the father-of-four said. "It was totally subservient to the government. It had to redefine itself and it was not easy. "Many community leaders had been compromised. But this was the price to pay to have a community at all." Nowadays the Jewish populace is growing. Jewish life in Poland - a country that once housed three million Jews until it was decimated by the Holocaust - is re-emerging. Konstanty said: "We, the religious, are a minority in the community, but we are its visible face. "Though the secular people resent being represented by the beards." In 1992 he joined the staff at Gazeta Wyborcza, Poland's biggest selling daily newspaper, for which he reported on the Yugoslavian civil war in the early 1990s. The bitter ethnic conflicts in the Balkans offered a gruesome vision for Konstanty of the depths Poland could have plunged to had the Round Table Talks failed. He explained: "Yugoslavia was a generation ahead of us. Our dream was that we might become Yugoslavia. "Then it degenerated into bloody madness, and we saw what we had avoided. "Seeing genocide committed in Europe so close to home made me realise how precarious this continent is." As the eurozone tears itself apart, Konstanty, once again, fears for the future of the region. He said: "Historically our continent has not been good at tackling crises. "If there is a serious crisis we tend to go nuts. The wonderful news is that we haven't so far. "Today's debate seems to be that Europe is not going to work. But I think that European integration is one of the most extraordinary inventions in history "Never before have different nations pooled their resources to such an extent." Still a journalist and columnist at Gazeta, Konstanty also edits the Polish-Jewish monthly magazine Midrasz, which he started in 1997, and runs the Warsaw office of the European Council on Foreign Relations. While his wife died last year, he battles on for the Jewish community. Barely a few thousand remain in the country that was once the greatest centre of Jewish religious and cultural life. He said: "We are a small and uninteresting community. "But it is the continuation of the Diaspora's most glorious community and because of the highly symbolic role it plays in Poland and Jewish national consciousness, we are literally several sizes larger than life. "The most important issue is not antisemitism, but demography. We're too few. The fact that people hate us is secondary "I'm not asking for Mount Everest. "I want 20,000 Jews. If we get that we can become a dynamic community once again."

|