|

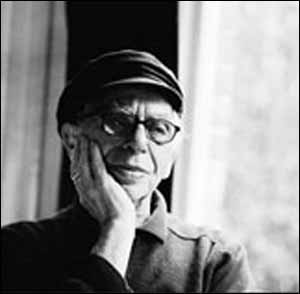

PROFILE Retirement? It's a dirty word to Bernard, 84 | |

FOR a man with scant formal education, Bernard Kops has etched an extraordinary career.

Born in the Jewish East End of London in 1929 - the year of the general strike - he grew up amid acute poverty. It was his local library in Whitechapel that proved a saving grace as he went on to produce numerous acclaimed plays, novels and poems in a career that has spanned more than five decades. And as he celebrates his 85th birthday on Monday, Bernard continues to write prolifically. His latest novel, The Odyssey of Samuel Glass, is due for release in April. "The word retirement is a nasty word," he said defiantly. The son of Dutch parents, he was the sixth of seven children. Growing up in Stepney Green, Bernard was struck by the tight community atmosphere of the predominantly Jewish area. He said: "There was a community spirit then. The tougher the situation was, the more the community held together. "When people moved away along the north- west corridor towards Hendon and Stamford Hill they lost that sense of community. "They lost the struggle and the politics. That's what binds a community together. "The poverty in the East End was terrifying. We were very poor, but overtly political. "Our occupation was our struggle." But the family managed to survive on food parcels from the Jewish Board of Guardians and visits to the local soup kitchen. While his Jewishness has made an impact on his life and work, the Kops household was not a religious one. "My father wasn't religious at all," he explained. "We didn't do seder night. "He thought that Jews were divided into two categories - religious Jews and political Jews. "We did go to shul occasionally though. We went on Simchat Torah to collect all the sweets." Despite the extreme poverty of his youth, Bernard was never a shrinking violet. He said: "I grew up with great confidence. My sisters used to fight to hold me. "In many ways the girls became like little mothers. That gave me a real sense of being wanted. "It meant I was an optimist and ultimately that helped me through life." A seminal moment in Jewish history in Britain was also a seminal moment in Bernard's life. The Battle of Cable Street, when the Jewish community of the East End blocked the path of Oswald Mosley's fascist black shirts, took place on Bernard's doorstep. And Bernard, never one to back down from the rough and tumble of life in the slums, flung himself into the action. He described the infamous Battle as "the first steps towards the Holocaust and to war". "I think the war had to be fought," he said. "Had England gone the way the others in Europe went, we would not be here today. "I worship Mosley for saving us in a way. If the others had got to power, we wouldn't be here." According to Bernard, the black shirts were not brimming with the ideological zeal of their leader. They were "down-and-outs looking for a foothold in society". The British Union of Fascists "gave these people hope and something to focus on". The BUF was an indicator, he claimed, of the rise of fascism. He said: "It was the fulcrum of a new time. These were the first shots of the darkness that was to follow." Attending school during wartime, Bernard proved himself a maverick. He was evacuated outside London with Stepney Jewish School, but decided to "disregard the blitz" and head home. "My nature has always been restless," he said. "I walked into a bombing raid and my parents were absolutely astounded. "I told them I had to come home because the school was bombed and two boys were killed, which was a big lie. "And that was the end of my education." Formal education over, he cemented himself as a student of the "university of the poor", Whitechapel library. He explained: "I was an empty vessel. I depended on the librarians to guide me." After 40 plays, nine novels and seven books of poetry, he evidently had paid meticulous attention to them. But he did not intend to be a writer. Growing up, Bernard recognised his detachment from the scenes around him. He could take a step back and look at situations from an alternative perspective. "I noticed I was watching my brothers and sisters," he said. "I wanted to understand that. I always felt alienated." Only after a trek across Europe did he stumble on his future career. Bernard said: "I happened to fall upon the greatest drama teacher in England. "She was Irish and called Murial. Then I started to read a lot and it carried me through. "But the biggest thing that ever happened to me was when my wife and I had a bookstall. "A man came up to the stall and he looked at the book I was writing. He said I had talent and wanted to show it to a publisher." Two days later Bernard took a phone call from Leonard Woolf of Hogarth Press to visit his office. The publisher expressed an interest in Bernard's work and "that was the way of becoming something". His experience as a Jewish writer is not detached from the collective European Jewish nightmare of the Holocaust though. Bernard explained that his immediate family came close to returning to his father's native Holland where they would almost certainly have been rounded up and sent to the camps. However, his father could not gather the money to go back home and they stayed put in London. He said: "I understood from then on that success can mean failure and failure can mean success. "The fact is we survived and not going to Amsterdam was a blessing in disguise. "It is the thing that has haunted me most." Not only did he survive, he went on to become one of the country's most revered playwrights, had four children, six grandchildren and two great grandchildren. He met his wife 60 years ago in a coffee bar. From the moment he saw Erica, Bernard was hooked. At that stage "I was going through my worst time - I was lost, starving and lonely". But on meeting Erica, he recalled: "My whole life changed. "She was very different from me and still is. There has always been vibrancy in our marriage. "I believe you need argument in a marriage. It's the cement. You don't need anyone who is another you - you need an opposite." Over five decades of marriage later and the family "has grown like a tribe". His debut play The Hamlet of Stepney Green, a humorous evocation of life in the East End through the eyes of a Jewish family, was performed in 1957 for the first time and remains his proudest achievement. But even as he turns 85, Bernard has no intention of slowing down. Next week he will be feted at the Jewish Museum in London with a reading of his first play and a celebration of his 85th birthday, but scoffs at the thought of retirement. "The word retirement is a nasty word," he declared. "You move away from anything that is important. "I take each day as it comes and make the most of it."

|